Continued from – “Tiger the Storm Magnet”

Inside it is cozy but jarring. Wet clothes drip onto wet floorboards. Pant legs and jacket arms reach out into space and fall limp after each roll, as if trying to grab onto something stable. Peter and Dana are tucked in their bunks, probably not asleep. I just came off watch, stripped my soaking pants, draped them strategically over my leeboard, and gratefully crawled in to radiate heat into the feathers of my duvet.

The edge of the monster low has caught us.

*******

The North Atlantic promises foul weather. I had anticipated it. In a sick way, I had hoped for it. My sail to Hawaii was a lazy river ride with just a splash of excitement. We slept through the nights, we reefed the main a handful of times, and the autopilot steered all but maybe six hours of 4,000 miles. I steered in 25 knots rounding South Point and felt like a hero, until I read a friend’s blog, who battled 40 knots just off Costa Rica, and I felt like a wuss.

So what was my motivation to experience weather? I cringe to think it might be partly recognition, and the sake of a story. A writer wants a good story after all. How many of my adventures do I seek just to round out a tale? That is part of it, for sure, but I know there is more. There is also the desire for freedom.

I want to know I can handle things. The fear of the unknown catapults me into the unknown, so I can know, and have less fear. Or a more informed fear. Every experience brings confidence. My childhood storms were handled by adults. More capable hands held the helm, or prepped for the hurricane. Now I am an adult, or at least I want to be. In my eyes and others’, I want those capable hands. I want to take care of others, to contribute. I want to feel equipped to handle my own adventures.

So to say that I hoped to pass through rough weather is uncomfortably honest, and a thought I did not share out loud, lest carry responsibility for its manifestation. “Pass through” being the key phrase, implying “to experience and complete”. It wasn’t the actual weather I looked forward to as much as the knowledge of how to handle a boat. To cross such a sea with such an experienced crew, I would have felt jipped not to see storm tactics in action.

Our first strong breeze, the night the boom broke, I disappointed myself. I lay frozen in my bunk, sleepless for my watch and what would be expected of me. From down below, all seemed chaotic. Dad scrambled and thudded across the pitching cabin top changing sails, frantic shouts shot from the foredeck to the cockpit, water roared past the hull. I tried to rest despite wide eyes and a tight chest. A state of anxiety I hadn’t felt in years. When I finally dressed and climbed out, I sat wedged in the companionway, harnessed in, huddled into the warmth of the dodger, watching the seas roll up from behind.

And somehow I was soothed. The anticipation of my mind met with the reality of the situation. Bodily senses awoke and switched off electric nerves one by one. I breathed in the stiff breeze. I warmed into my wet clothes. And my eyes watched the most amazing phenomenon as eight foot swells surrendered to the intelligent design of our hull.

Staring into these bullying seas, which poked and pushed and taunted us to spin and slide sideways down their menacing faces, I tensed and relaxed as they raced up, and then stopped, melting at the force of our displacement. Some hissed and growled, and curled their white lips, but upon meeting our gentle Tiger, took pause, greeted her as kin, and swerved aside, and we bobbed on like a cork.

Dark fell, and the frothing white caps morphed into the green glory of bioluminescence. Our boat slashed a swath of pixie dust through the stampeding ocean, our rudder striking a streak behind, and rioting waves roared avalanches of glittering green foam. The sea lit up with night life.

The occasional pest, however, came from an odd angle, hitting with a thud, followed by a suspended silence as the sheet of water soared through the air, and finally shattered on the cabin top or cockpit. Worse was the unrelenting bully who succeeded in skidding us sideways, as the helmsman fought and groaned to keep the wheel in place.

I did not steer that night. I sat awake as the second person on watch, but after three days of seasickness, and breaking the boom, I felt incapable of keeping the boat safe. That storm passed, and in its wake I felt inadequate, less of a sailor than before.

*****

The “complex low” spanned nearly 1,000 miles. We expected it Tuesday, but I awoke for my afternoon watch Monday to 15-20 knots south wind, Tiger skipping and bouncing over the mild seas, rain filling water jugs. A pre-watch anticipation was standard by now, but only because apparently there would be no bikini weather this trip. I felt the typical whineyness related to soggy pants and cold, wrinkled feet, but without the previous paralyzingly anxiety.

The five days since our first blow had provided a comprehensive curriculum of shifty winds and “training waves”. Driven by my last defeat, I focused my watches on mastering the feel of the boat. I took the helm from the Aries and determinedly practiced steering the rolls. This usually drew raised eyebrows and side glances from Peter, who finally came out to coach me.

“The rudder is like a big door under the water!” he said, New York sass flaring. “Every time you turn the wheel, you make more frequency. Just hold it steady and let the boat roll it’s natural rhythm.”

“But…but…” I’d argue, showing him what I was trying to achieve, until bit by bit, day by day, I saw that of course he was right and I learned to resist my reflex to control every motion, which just made it worse.

Similarly, I plagued Dana with questions about wind direction and sail trim. I watched the wind vane, cautious of sailing by the lee, and relaxed into downwind steering. With Dad I just chatted and observed, taking notes on the ease with which he sailed his boat, seated off to one side holding the helm with one hand, barely flinching at the strong rolls.

So I stepped up to my watch damp, but confident. Dad put a second reef in the main and I took the helm from the Aries as the wind crept up, then crept some more. Kept on creeping, but so slowly that I didn’t notice I was fighting the helm. I just thought it was part of strong wind sailing. Dad and Dana popped out to survey the forces they felt below, and deemed it time to set the third reef and the storm jib.

As the wind wavered around 30, blowing the ocean surface in furry shivers, they fumbled on deck with whipping sails, and I gripped the helm trying to keep them safe. To keep the wind behind enough to relax the sails, but not so far behind to jibe the boom in their faces. That marked my most intense moments of the whole storm. Once everyone was safely back in the cockpit, I headed up on course and started to have fun. Rain pelted from the south, keeping the seas mercifully flat, and a few dolphins zipped at our bow, distracting and exciting me. I steered until I was cold and soaked and proud. “Thrilled” as Joshua Slocum would say. (Meanwhile, as I struggled with 30 knots, he had just battled through the Straight of Magellan at Cape Horn, only to be pushed back by a gale to start all over again.)

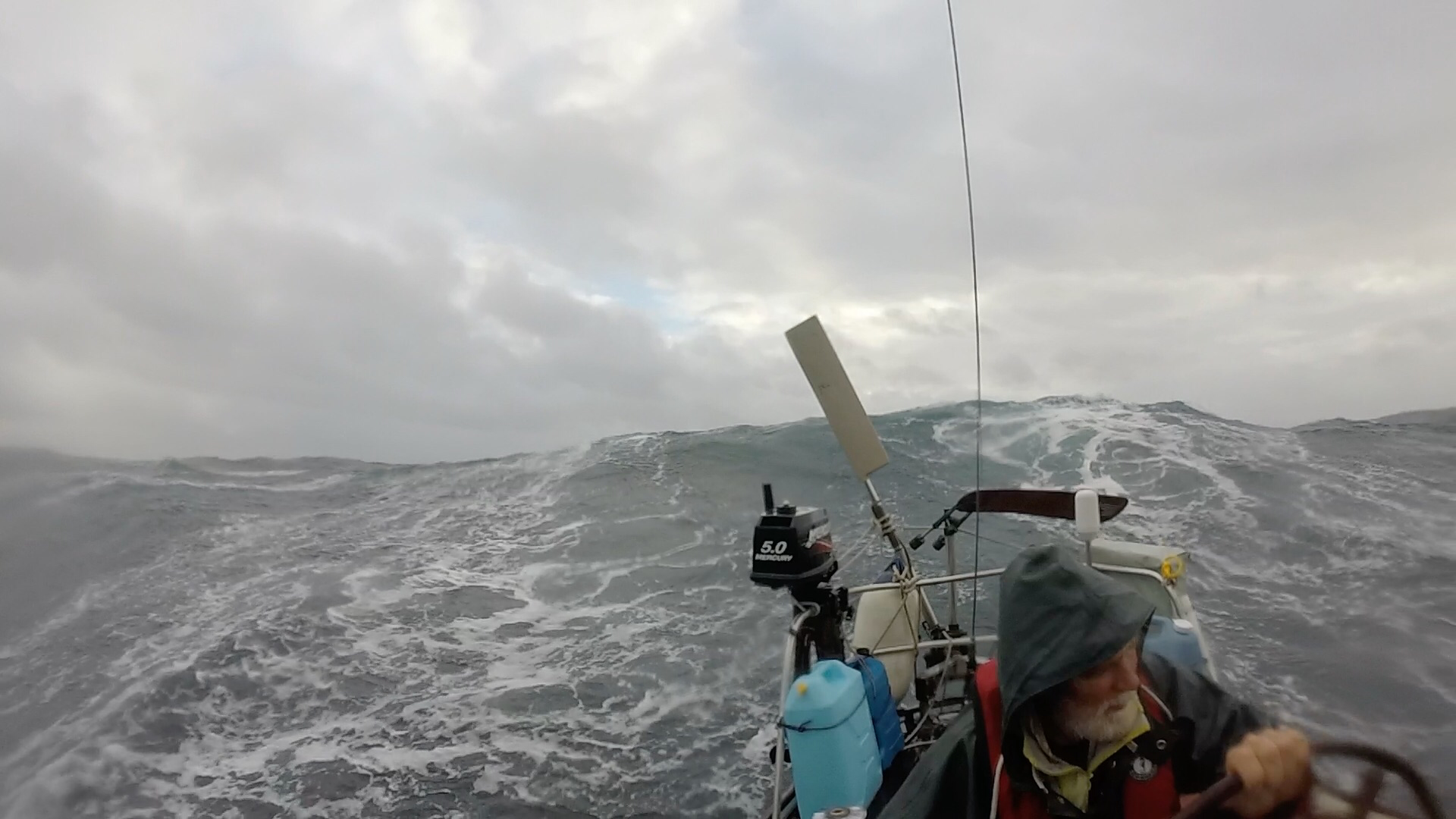

Ours was a tricky little storm. I read afterwards that “complex low” means a system with two or more defined areas of low pressure. That night the wind spun from south on our beam, to west and dead behind. The initially flat seas gave way to swells predictive of much stronger winds…somewhere. Some crept up steep and alarming, but most just lumbered past or crumbled to our sides, 15 foot rolling hills and us a grazing beast trying to keep its footing.

Winds blew strong, then stopped altogether, as the storm took a breathe, leaving us uncomfortably underpowered for the conditions. “Like feeder bands in a hurricane,” said Dad ominously. And she’d exhale, sending us along again. The wind felt gentler from our back, so the 30’s felt like 20’s (thirty is the new twenty after all). Forecasts for this thing ranged from gale to storm. We steered and waited in suspense, like being in labor, unsure where we were in the process, and if the worst was still to come.

Those two days we slept little, with two people awake at a time. Two hours steering, two hours sympathizing (and making tea and checking that the helmsman was still there after particularly pushy waves.) We were exhausted, and Peter especially who couldn’t sleep at all with the rolling boat. I started to take his snoring as a good sign.

But despite exhaustion, I was keen to test my skills and my attitude. Taking the helm settled me into a focused rhythm, energized by the air and exertion. I was elevated by the thought that others were warm and safe in their bunks. I felt like a caretaker. And then at the end of those two hours, I felt like I’d earned my own warm bunk time, and I’d dive in without hesitation.

As I crawled in the second night, I called up to Peter, “Tomorrow it’ll be bikini weather!” Naive and hopeful. I awoke just after dawn to his cursing. The storm had swept away her skirts of wind, but left a trail of sharp, confused lumps. Peter hadn’t slept for nearly a day, and his tired mind battled the sluggish boat against the slappy waves. Dad the compassionate captain rushed to relieve him and turn on the engine. I thought this would be over by now!

But as we fretted with infuriating swells, calm moved in. The moon, who had been secretly growing behind the curtain of clouds, finally broke out to show her face for the first time since New York. Gulls bobbed on the surface, dancing away across the water on tiptoe, wings spread to levitate. Sharp little terns dove and discussed if our windvane was some jackpot of an insect and our sails some mothership of a white bird. The seas finally wore themselves out, settled into long, rolling undulations and a steady northeast wind, just as we had hoped. The Aries could finally take over. We relaxed together in the cockpit, Dana cleaned, and I slept and slept.

The next day, Dad finally got to shake the reef out of the main, and I saw my first sunrise break above a cloud bank. Somewhere on the coast of Ireland, a nasty low pounded the shore with an unusual summer swell. Had we skipped our stop in Newfoundland, we would have been caught near shore with an unfinished drogue. And then, exactly two weeks later, Hurricane Gert traced our track across the ocean. Sometimes you gotta think that somebody’s watching out. And not to take your luck too much for granted.

I got my rough weather, just enough to feel more confident as a sailor. And to think that maybe a good sailor doesn’t ask for rough weather.

Continued in – “Ireland!…Now What?”

2 thoughts on “Foul Weather Finally”